The quadriceps (while technically four muscles, for this post we’ll view them as one) get the most attention after reconstructive anterior cruciate ligament surgery. And the quads do need work. Within hours after waking up from anesthesia, you can see their activation diminish.

However, this can be quickly remedied. Just a few minutes later:

If left alone for a while, like how many wait a month to start their rehab, this can become quite problematic.

The other issue with the quads is of course atrophy. Similar to the above though, if you don’t wait to begin rehab, this can be mitigated. Some atrophy is likely going to happen no matter what, but it shouldn’t be severe, because we shouldn’t be severely lessening how much we work the leg.

So far we’ve only discussed consequences of ACL surgery. We haven’t actually discussed the ACL. For instance, what musculature helps the ACL do its job? Shouldn’t we be giving attention to that area?

–

What does the anterior cruciate ligament do again?

The ACL goes from the back of the femur to the front of the tibia. Front view:

Side view:

The ACL subsequently prevents the tibia from going in front of the femur. It pulls the tibia back to the femur.

Animation made from this video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JWI_Qghqclw

To test if an ACL is torn, an orthopedist gauges how far they can pull the tibia forward relative to the femur.

If that motion is really lax, there’s probably a tear.

-> The ACL could also be excessively stretched out, functionally making it torn. A radiologist could plausibly see an intact ACL on a MRI, but an orthopedist can easily feel if it’s torn. This actually happened to me.

–

Hamstrings

They come down the back of the leg, connecting at the bottom of the knee:

They also run a little forward, moving towards the front of the shin some:

We can see the hamstrings line of pull is very similar to the ACL. In fact, when you get your ACL tested, the orthopedist will insure your hamstrings are relaxed, so you don’t get a false negative. If they’re contracted (common for a person to tense up when an injury is being assessed), the knee may not appear as unstable as it truly is.

–Why you shouldn’t bother with a non-orthopedist testing your ACL

Thus, we can see we want strong hamstrings, to help pull the tibia posteriorly and offload the ACL. This is one hypothesis behind females being more susceptible to ACL tears- their hamstrings are weaker.

An interesting aspect of the above study is while female athletes who had weaker hamstrings went on to incur more ACL injury risk, these females did not have weaker quads. Furthermore, the females who did not incur greater ACL injury risk had weaker quads, but not weaker hamstrings.

- Weaker quadriceps and ACL injuries = ok

- Weaker hamstrings and ACL injuries = not ok

–

Back to the quads

The line of pull of the ACL and hamstrings is pretty obvious, but not with the quadriceps.

–Lines of action and moment arms of the major force-carrying structures crossing the human knee joint

Here is our tibia, which is the bottom of our knee. Anterior is the front, posterior is the back. So we’re looking at the side of the knee:

Let’s think about the ACL as the knee bends.

We can see the line of pull of the ACL isn’t going to change direction. That is, it’s always going to be pulling the tibia back:

0 to 120 represent degrees of knee flexion. The black line where the ACL is pulling at those degrees. So 0 is where the ACL is at no knee flexion. Then we look at how that changes as the knee bends.

When the knee is at 0 degrees knee flexion (it’s not bent at all), we can see the ACL is pulling back at about a 45 degree angle (pink). Then once at 120 degrees, it’s pulling the tibia back at essentially parallel to the ground (blue):

Point being, no matter what, it’s pulling back.

Hamstrings:

Different angles, and a lower insertion point than the ACL (the hamstrings aren’t as effective as the ACL for this reason), but the gist is the same- always pulling backwards.

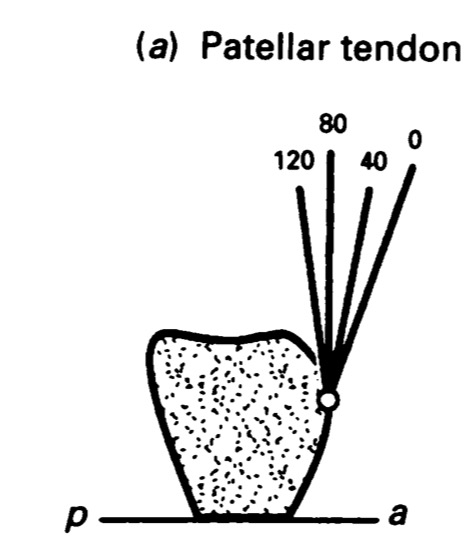

Quadriceps, which connect into the patellar tendon:

Different! At 0 and 40 degrees, the pull is forward.

Up until ~65 degrees knee flexion, the quadriceps are pulling the tibia forward. It’s counteracting the ACL. After that point though, and the quadriceps are helping the ACL.

–

60+ degrees knee flexion is a fair amount. In most sports, we spend most time above that.

About as deep we get. Even still, notice the guy’s left knee, the more flexed one, *isn’t* being loaded. It’s off the ground.

Julian Edelman just tore his ACL. He’s not more than 65 degrees:

We can now see why having weak quadriceps relative to hamstrings could have been advantageous for those girls who didN‘T tear their ACL. The quads can HELP tear the ACL at higher knee flexion angles!

Thus, if we had to pick a muscle, or group of muscles, to anoint as most important after ACL surgery (or prophylactically), we’d pick the hamstrings. Luckily, in the real world we can focus on both. The point here is people tend to obsess over the quads after surgery. Don’t neglect the hammies!

–

Bonus section: should we avoid hamstring grafts then?

A hallmark of ACL surgery is the site where we get our graft, almost always the quads / patellar tendon or hamstring / gracilis, gets weakened. Many times to a degree we can’t overcome it. Cutting part of your body off can do that.

Should we avoid hamstring grafts then? Considering it could weaken the hamstrings? A patellar tendon graft can weaken the quad, but is that actually advantageous? It sets us up to more likely have a better relative strength profile i.e. quad to hamstring ratio.

The quick answer here is a lot of ACL studies don’t find a noteworthy difference in failure between grafts. So most people don’t need to worry about it.

Longer take: Muscle strength is only one factor. Graft strength favors hamstrings over patellar.

And strength is only part of the equation. What’s just as important is how quickly the hamstrings turn on, as well as how much they fatigue. After all, when playing most sports which commonly injure the ACL, we’re not engaging maximal strength much. We’re having to consistently engage in proper neuromuscular control, and fatigue is when most injuries happen. Strength can be a proxy for these traits, but it’s not a direct measure.

Next, strength might go down, but if you’re only down say, 5%, that might not matter. 20%? That’s a different deal. If you have a shitty rehab, then sure, this matters more, but we’re assuming a solid rehab.

Plus, other hamstrings which weren’t cut, the biceps femoris and semitendinosus, can pick up the slack.

-> The tendon cut for the graft can also regenerate.

–Regeneration of hamstring tendons after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction

My personal ACL-hamstring-graft-experience is my hamstrings barely ever have any problem with fatigue, and the timing comes back with dedicated rehab. The graft area always feels different when doing intense strength exercise, but I do feel like I’m close enough it’s not a problem. It feels different, but I can do the work. It’s not like I go running and feel “Man, my hamstring is noticeably weaker.” I have to really push the envelope lifting wise, with particular movements, to feel that.

–Dealing with weird sensations after ACL surgery

Also, again, it’s the relative strength. So you could have weaker hamstrings after rehab, but if you also have weaker quads (where the leg is just generally weaker), you might be fine.

-> This stuff gets tricky: after an injury, many give that area more concern. For instance, after a quadricep graft, it wouldn’t surprise me if patients / therapists gave more attention to the quad than the hamstring, inadvertently making the quad relatively stronger. Conversely, hamstring graft and you might disproportionately strengthen the hamstrings. I know I had a phase where I became much more focused on the hamstrings than the quads.

Finally, while I’ve gotten back to very intense exercise, I’m not playing NFL football. At the elite level, this could warrant leaning towards bone-patellar-bone grafts, which is what elite athletes do. And the younger the person, the more graft failure is a concern, because they’ll be pushing the graft more than anybody. You might find some differences between grafts in that situation.

-> This is why elite athletes don’t use cadaver grafts. Risk of failure is alarmingly high in active populations. Graft decisioning is all about trade-offs.

For everyday people though, even if there is a higher risk of failure in the graft, it tends to be quite small overall.

In that study 3.9% of hamstring patients had a failure while 2% of patellar tendon patients did. That’s a wash for an everyday person.

However, long term, such as arthritis rates, the scale tips towards hamstring grafts. When you put a drill in your kneecap, the knee may be more likely to have issues down the line. Hamstring grafts don’t necessitate drilling the kneecap.

–Fifteen Year Prospective Comparison of Patellar & Hamstring Tendon Grafts for ACL Reconstruction

With this surgery, longterm is where most people’s thought process should be.

Also note in the above study the opposite knee was much more likely to have an ACL tear in patellar grafts. We’ve been talking about the lack of importance of the quad in the operated knee. We haven’t touched on the other leg! Say, if the quad isn’t as strong, or if the knee has more arthritis / pain in it, that may make you more likely to lean on the other leg compared to if the hamstrings aren’t as strong, causing an increase in injury in the opposite side.

So picking a graft isn’t that straightforward. Surgeons have also progressively moved towards hamstring grafts. (My experience watching surgeries says hamstring grafts are significantly easier to harvest.) Where again, for the average person, that’s also going to cause a bias towards using hamstrings.

–Reconstructive ACL surgery: Which graft should you use?

***

Learn about the most important phase of ACL rehab

***

Posted on December 4, 2017